Ritual for Reformers? On the evangelical recovery of liturgy

Is a renewed evangelical interest in liturgy and ritual helpful, or a dangerous step back to pre-Reformation Christianity?

Thanks for reading! Read on for my evolving views on liturgy, but first, a few updates…

Thank you, Tim Keller

I’m immensely grateful for the life and ministry of Dr Timothy Keller. I saw the news while at Hutchmoot, and many of us there have been profoundly touched by his ministry and writing.

He was wise Bible teacher and thoughtful and nuanced in his cultural engagement – he’s profoundly shaped my ‘theological vision’ as he terms it in Center Church. I’m grateful to God for his gift of Keller to the church, and I pray for Keller’s family and church now as they grieve him, all while remembering the resurrection hope that he held to so firmly.

You can hear me talking about Tim Keller’s Center Church as one of the books that shaped me on TWR’s The Books that Shaped Us podcast, recorded last summer:

Hello Hutchmoot!

I’m writing this on my way back from Hutchmoot UK 2023. It was a great time of creative community! I was blessed by hearing Doug McKelvey talking about weakness, and how our weaknesses are not barriers, but divine invitations to depend on God and draw near to others in community. I enjoyed hearing Andrew Peterson talking about the art of writing. I loved having many fascinating conversations with friends old and new. A big wave to everyone I met there!

A request

I believe my calling is to engage creatively and critically with culture from a Christian perspective, and to help others to do the same.

If you value what I’m doing on Bigger on the Inside and Imaginative Discipleship, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to help support me in my work.

Your financial support will help me continue and build on what I’m doing to explore culture and point people to the reality and relevance of Jesus. My liturgy article below is my first paywalled article, but you can access it with a free trial.

Also, if you choose to become a Founding Member with a larger annual subscription, I will send you a selection of books relating to the themes of this newsletter. I’ll get in touch to make sure I pick books that you haven’t already read, please bear with me if it takes a few days to get in touch!

Rediscovering liturgy

Evangelicals have long been suspicious of ritual, liturgy and spiritual disciplines. But there’s been something of a sea-change in recent years, with a renewed interest in these practices among evangelicals – myself among them. What should we make of this – is it passing fad, dangerous flirtation, or spiritually helpful?

My journey with liturgy

I first encountered liturgy at L’Abri through the chapel services there, and at the nearby International Presbyterian Church, and while it seemed foreign to me at first, I discovered a real richness to it that can be lacking in the very informal independent evangelical style that I’m used to.

I’ve also been using the Church of England’s Daily Prayer app regularly in my quiet time for several years now, and it helps me feel more connected to a wider body of believers than just taking my own individual meanderings through scripture, and gives me more Bible and less pre-packaged answers than your average evangelical ‘Bible reading notes’.

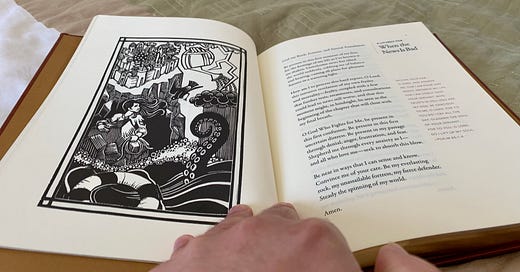

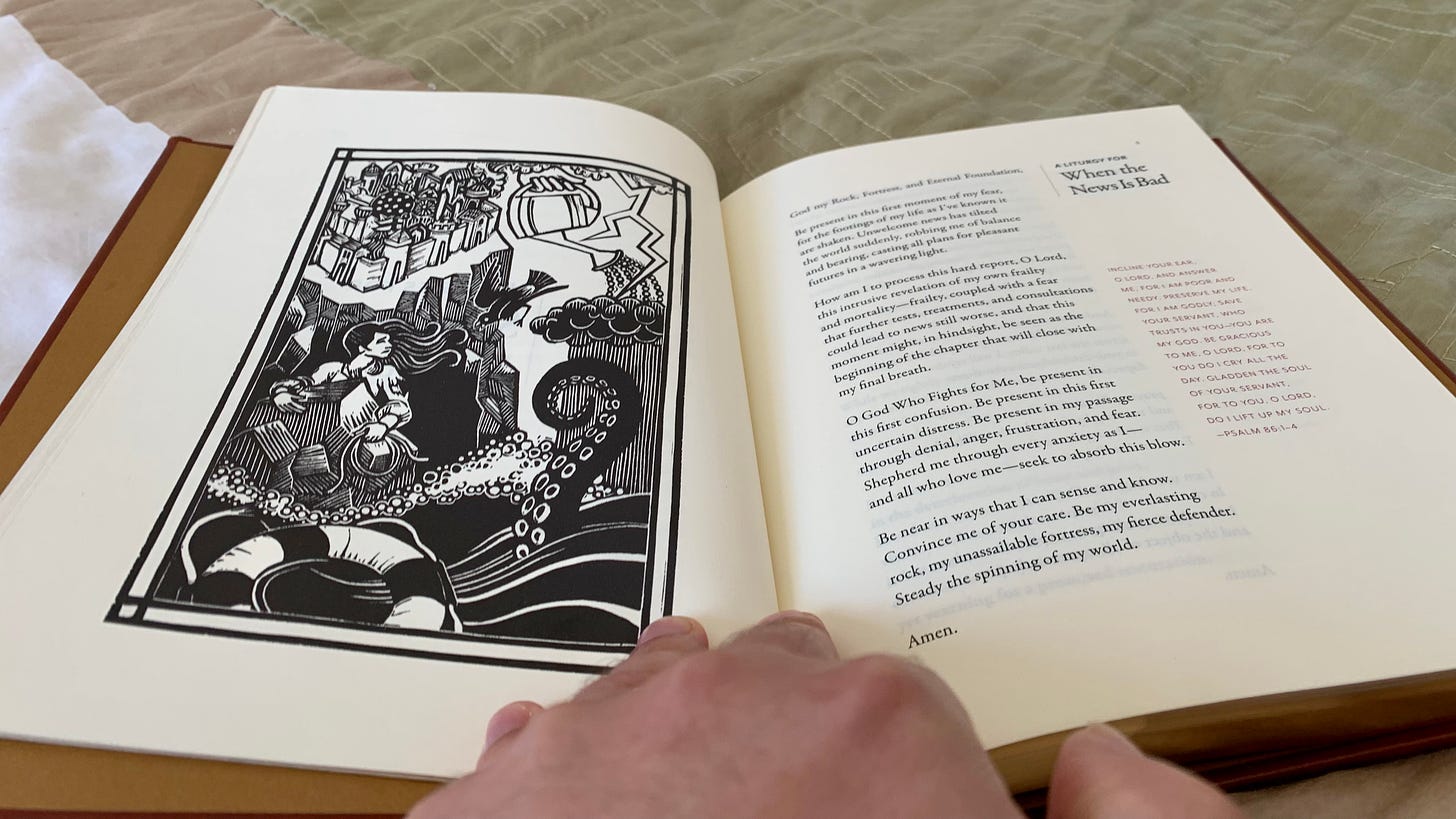

I also appreciate the deeply integrated spirituality of Every Moment Holy, which has liturgies for all sorts of occasions, from making coffee and changing nappies through to coming to term with the death of a dream or facing the loss of a loved one.

Voices for and against

One influential voice in support of liturgy has been James K A Smith’s book You Are What You Love (Brazos Press, 2016), which argues that we need to recover these practices for faith to flourish in a secular age. I found Smith’s book helpful and convincing. But not everyone is persuaded: its review by Pete Woodcock and Tom Sweatman in Evangelicals Now under the title “Reversing the Reformation” (paywalled) called it a “dangerous book” that “could even lead people back to pre-Reformation religion”.

Now, I know Pete and Tom from serving on the Christian youth camp Contagious with them and have a lot of respect and affection for them, and take their concerns seriously. But does this reflect what is Smith really saying? Is recovering liturgy a betrayal of our Reformation heritage, or essential for shaping our hearts to love God?

Shaped by our loves

Smith’s starting point shaped primarily by what we love, more than just what we know. We are shaped by what we worship. Christians have sometimes adopted the modern assumption that humans are primarily “thinking things”. Our efforts at sharing the Gospel have focused on communicating the right information about God, and expected changed minds to automatically produce changed hearts and lives.

But we usually find there is a gap between what we know and what we do. According to Smith, our actions are driven less by our conscious beliefs, and more by some vision of the good life, “a picture of flourishing that we imagine in a visceral, often-unarticulated way” (p. 24) – it trains us to desire some “kingdom”. We live toward this “kingdom”, a love that is “less a conscious choice and more like a baseline inclination, a default orientation that generates the choices we make” (p. 31). The kingdom that the Bible offers us is that of communion with God, knowing and loving him.

Hearts seeking God

This emphasis on the heart has a long heritage in the Reformed tradition. John Piper’s Desiring God is based around the idea that true worship is supremely treasuring and delighting in God. This emphasis goes back to Jonathan Edwards, Augustine and indeed, to Paul, such as in Philippians 1:9–11, where Paul’s prayer is “that your love may abound more and more in knowledge and depth of insight”, situating knowledge within the context of love of God. Knowledge is essential, but it is intended to prompt and enrich our love for God.

According to Smith, however, we can’t just think our way to loving God; we need to intentionally practice habits that will calibrate our hearts towards him, or our hearts will be shaped by other forces.

“Secular” liturgies

We’re swimming against the tide: Smith argues that we are constantly being shaped by “secular” liturgies, such as going to the shopping mall (or shopping centre, for British readers!). The rituals of shopping train our hearts to love the satisfactions of material choice and consumption. The rituals of checking your smartphone repeatedly through the day, for many from first thing in the morning to last thing at night, train our hearts to love the sense of connectedness and social validation that they offer us.

In this context, Smith uses “liturgy” as “a shorthand term for those rituals that are loaded with an ultimate Story about who we are and what we’re for” (p. 70). “Secular liturgies” are often powerful because they go for the gut, engaging the body and the senses, appealing to the imagination and desires. And most of the time we aren’t even aware that they are training our hearts and desires.

Reclaiming liturgy

For our hearts to be shaped towards loving God, rather than being misshaped by secular liturgies, Smith says that God gives us “Spirit-infused practices that will reform and retain your loves”. God meets us “with counterformative practices, with hunger-shaping rituals and love-shaping liturgies” (p. 95).

By “hunger-shaping rituals”, Smith has in mind spiritual disciplines – habits of prayer, fasting, worshiping, serving, learning and so on. By “liturgy”, Smith has a broader meaning in mind than just formal liturgies (though he has a lot to say to commend historic Christian liturgies). He’s talking about our worship, emphasising that is not just the music or singing as opposed to the sermon as “teaching”, but the whole pattern of the church being gathered together. Neither is worship simply us expressing ourselves to God; worship is God shaping us by his Spirit through “practices of prayer and song, preaching and offering, baptism and communion”. Smith’s central argument is that “the church’s worship is the heart of discipleship” (p. 96).

But to have its full intended effect, it needs to be “embodied, tangible, and visceral. The way to the heart is through the body” (p. 114). Physical objects and images can all play a powerful part in worship. Worship is also most powerful in community, and should include the down-to-earth practices of eating together, praying together, singing together, thinking and reading together. In the body of Christ is where our love for God most naturally grows.

Smith acknowledges that for “those of us who are Protestant evangelicals, ‘liturgy’ is going to sound like a bad word… ‘vain repetition’, the dread ‘religion’ that is an expression of human effort” (p. 97). But he argues that the Reformers in rejecting medieval Roman Catholic worship weren’t trying to be antiliturgical but to be properly liturgical.

Undermining the Word?

What are we to make of this? In their review, Pete and Tom criticise Smith for the “strong sense that preaching, teaching, Bible reading, study and memorising are insufficient”. But Smith is at pains to emphasise the importance of preaching, Bible study, daily Bible reading, Christian books and conferences, and other means of learning (p. 16). To say that worship must be more than intellectual does not imply the Word is unnecessary or insufficient. Rather, it is acknowledging the insufficiency of applying the Word to anything less than the whole human person.

Used properly, liturgy is not an alternative to Word ministry, but a multi-sensory delivery mechanism for the Word. Rituals, images and objects should never replace or obscure the Bible, but can be effective ways of presenting it more fully and bringing its truths alive. I think it’s particularly helpful to recover the more regular (ideally weekly!) celebration of the Lord’s Supper. I was for several years part of a Brethren-heritage church which had the Lord’s Supper (including time of open worship) every week, although it was very anti-liturgical in other ways. The ‘ritual’ of Communion is both thoroughly Biblical – ‘do this in remembrance of me’ – and gives taste and texture to God’s promise of grace to all who trust in the body and blood of Christ. Communion is the promise of the Gospel made tangible.

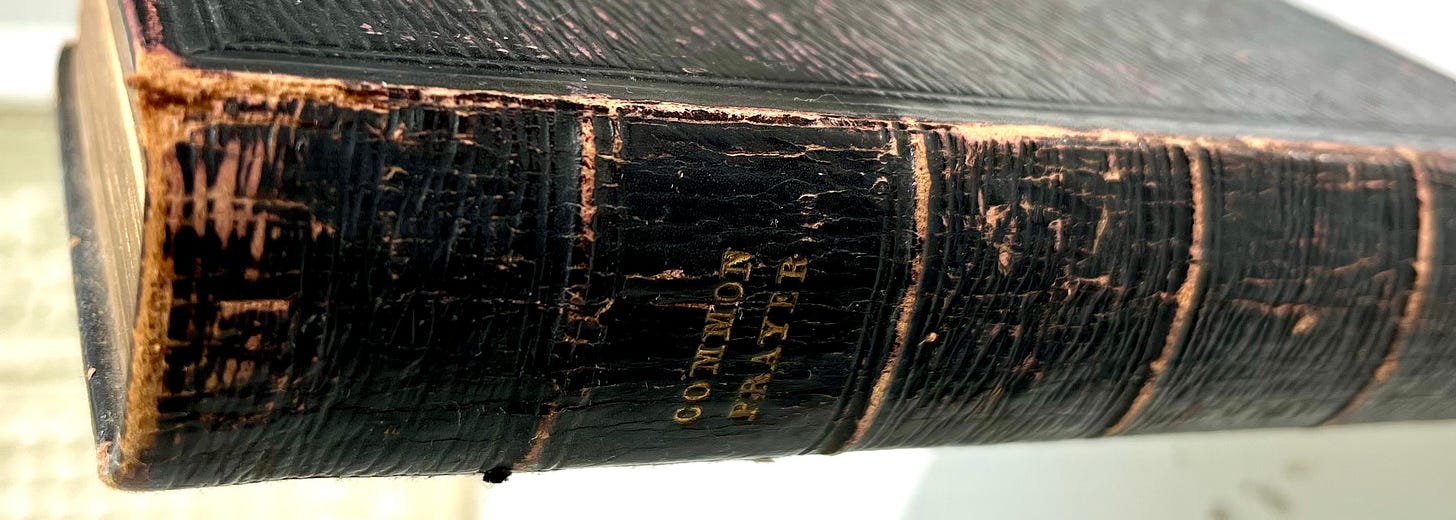

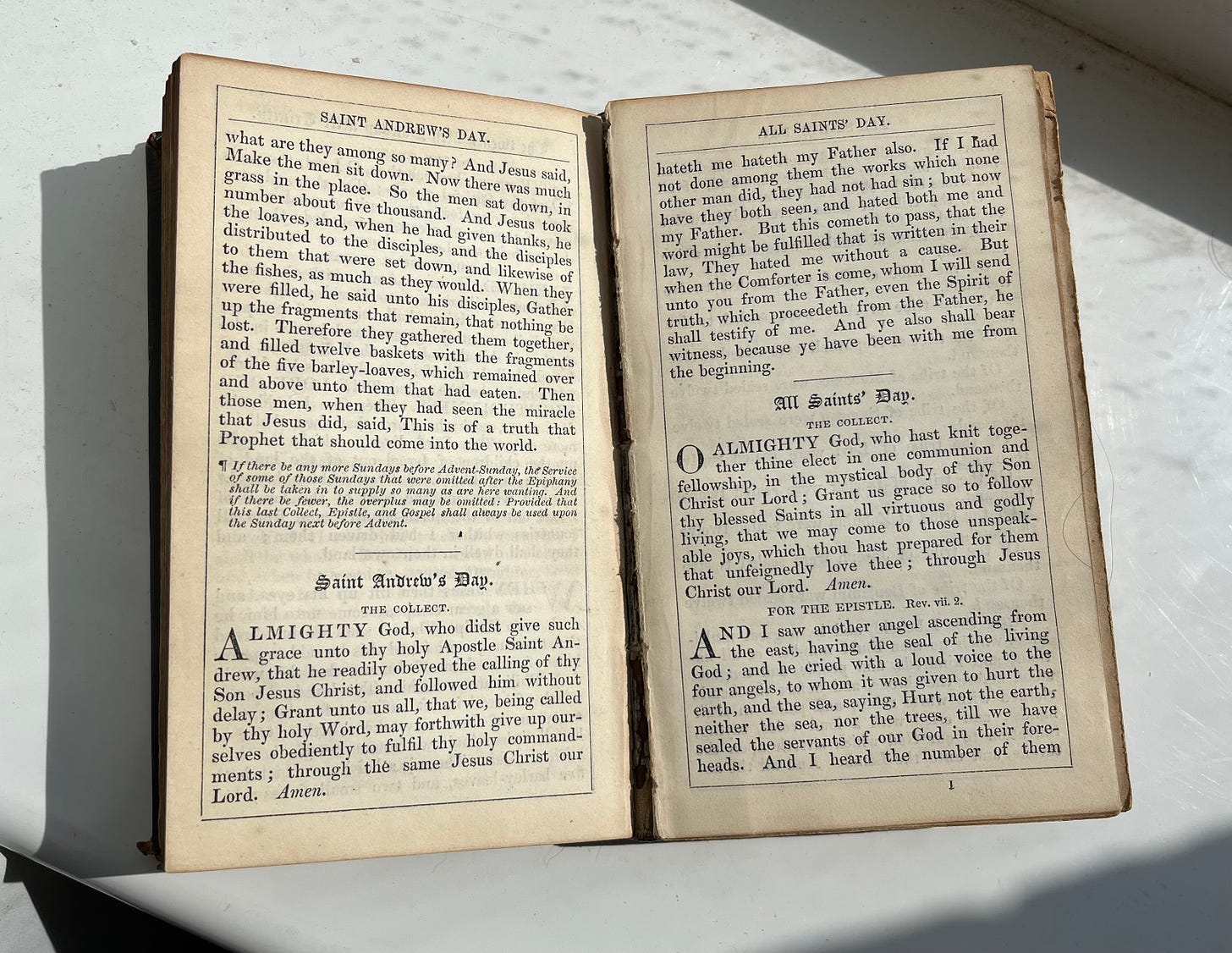

We also have clear historical examples of the Bible-soaked richness of Protestant liturgies such as the Book of Common Prayer. While many evangelicals will differ with its theology on various points, the Word is central to both to its form and content. To dismiss liturgy as inherently suspect is to throw out the liturgical baby with the ritualistic bathwater.

Liturgy, ritual and heart-change

The other danger of liturgy that Pete and Tom warn against is that is can become a means of self-righteousness. Smith too acknowledges the danger of “naturalizing” worship to something down to merely human effort (p. 97), though it’s a pity he doesn’t expand further on the necessity of new birth.

Liturgy can’t save you – only the gift of a new heart by God’s grace at work in us can do that. But just as we are not saved by good deeds, but for good deeds, we are likewise saved for worship. Liturgy and spiritual disciplines can’t create new spiritual life or hunger for God, but they can help cultivate it. If our love for God is like a vine planted by the Holy Spirit, then liturgy and habits are like tending the soil and putting up a trellis – they don’t give life, but they support it and help it grow to its full potential. Liturgy and habits aren’t about creating inward change by human effort, but working out the change God has already begun in us.

Much to gain

You Are What You Love is a provocative and helpful look at what worship is and how it shapes us, even if you don’t ultimately agree with Smith’s suggestions for what formative worship should look like.

Liturgy apart from God’s grace and God’s Word could indeed be spiritually dangerous (as could any form of Christian worship and discipleship divorced from spiritual reality!), but that’s not what You Are What You Love is recommending, and what we might regain to my mind outweighs the risk of empty ritualism.

Smith’s work is an important prompt to help us as evangelical Christians to recover liturgy, and rediscover it as a powerful way of applying the Word more deeply, and growing our love for God more richly.

What do you think? Are you from a liturgical or non-liturgical tradition? How have your convictions or preferences about worship changed? Let me know with a comment or in the chat!