The Sandman's Missing Basic Plot and the Meaning of Reality

Neil Gaiman's The Sandman is all about story. So why is one of the seven basic plots missing, and what does that have to do with the new book Reality and Other Stories?

Before I get onto The Sandman, a couple of quick things to note. Firstly, hurrah! I’ve reached 100 subscribers! Thank you all for reading, and a special welcome to those who have signed up recently in wake of the Fieldmoot online conference. If you’re not familiar, check it out at www.fieldmoot.com, including the video of my Imaginative Discipleship lecture!

Just a quick PSA: My wife and I are expecting the birth of our third child around 15th November! So normal service will be interrupted over the coming weeks. I hope I’ve got enough material already recorded to keep Imaginative Discipleship podcast episodes publishing on a fortnightly basis – but we’ll see how I get on as I reenter babyland! Now, on to the main event…

How I discovered the Dreaming…

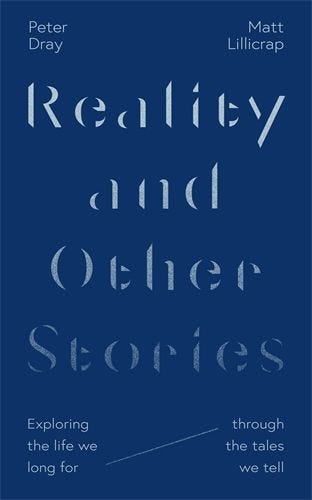

Stories shape us and give us meaning – a theme that is explored both in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, the hit comic series now adapted for TV by Netflix and just renewed for a second series, and also in Reality and Other Stories by Peter Dray and Matt Lillicrap, out now from IVP.

I really enjoyed the faithful but not slavish first season of The Sandman on Netflix, so I’m delighted that the story will continue in TV form with a season 2. In many ways, I have a very different perspective on life than that of Gaiman’s epic, as I will get to, but I think it’s a powerful story that rewards thoughtful engagement. These comics were formative for me as a teenager. I first stumbled upon The Sandman comics in my local library in the early 2000s, starting with the trade paperback of The Doll’s House. I was fascinated by this dark and magical exploration of dream and story and ended up getting the complete run in the deluxe leatherbound Absolute editions.

This week I unpack the connections between The Sandman, the seven basic plots, and how they reveal the human longings that might just give us clues to the meaning of reality…

What is The Sandman?

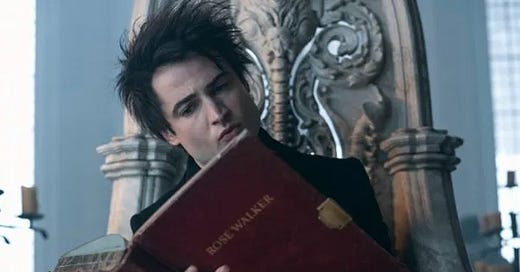

Neil Gaiman’s epic mythopoeic fantasy tells the story of Dream, or Morpheus, king of the Dreaming. He rules the realm where sleepers come to when they dream. Morpheus is one of the seven Endless, along with Destiny, Death, Desire and the rest. He is often encountered through the perspective of human characters who stumble across the reality of the Dreaming, such as Rose Walker, a young women born a dream vortex whose very existence threatens the fabric of reality, or Lyta Hall, whose baby conceived in dream is claimed by Morpheus as his own.

The Sandman is all about the power and peril of dreams– the myths and stories we tell ourselves, from gods to superheroes to personal narratives. As critic Damien Walter put it, The Sandman makes us consider the ‘high cost of fantasy’. What do our dreams give us, and what do they take from us in return?

The Seven Basic Plots

Reality and Other Stories also probes the meaning of myth and story. It draws on Christopher Brooker’s The Seven Basic Plots to ask, is it coincidence that the same seven archetypal patterns repeat over time and across the world? What if these stories are not only revealing something about human psychology, but also give us clues to the meaning of reality? If the world really is a story, then what kind of story is it?

These seven stories are:

Overcoming the Monster

Rags to Riches

The Quest

Voyage and Return

Comedy

Tragedy

Rebirth

Let’s turn to how these surface in The Sandman…

The many plots and genres of The Sandman

Over its 75 issue run, The Sandman covers many different stories. It starts as part of the

DC Comics universe but becomes its own thing, drawing on myth and legend, religion and pop culture, in a heady mix.

It’s not surprising that The Sandman covers most of these seven basic plots. Season 1 of The Sandman on Netflix gives us Overcoming the Monsterwith escaped nightmare, the Corinthian, who inspires human serial killers to their twisted dreams. Rose Walker has a Rags to Riches subplot with the discovery of a long-lost (and wealthy) elderly relative. Morpheus embarks on The Quest to retrieve his lost tools: his pouch of sand, his helm and his ruby. This includes Voyage and Return to Hell itself, and his confrontation to recover his ruby involves near-death and then Rebirth.

Finally, we get hints of the dark decisions that lurk in Morpheus’s past, and the question of whether he can change - will his story ultimately turn out to be one of Rebirth, of embracing change, or one of Tragedy, where his inability to change leads to his downfall? Comics fans will know how the ending plays out, but I won’t spoil it here! Suffice to say Morpheus’s story builds to a clever and complex finale by the end of the series that brings these conflicts to a head.

The Case of the Missing Plot

What might be surprising though is that one of the seven basic plots is missing: Comedy.

There are funny moments in the Sandman, of course, like Dream getting a telling-off and stick of bread thrown at hm by his sister Death for being a pathetic excuse for an anthropomorphic personification. But Comedy in the technical sense is about a story where misunderstandings are resolved, everything makes sense, and the characters gain their happily-ever-after.

But here are no happy endings in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. There are moments of resolution, even of happiness, but they are never unambiguous, and always temporary.

That’s a feature, not a bug. The Sandman is a fantasy epic that’s aggressively anti-escapist.

We’re told the following about Bette, a waitress who fancies herself a writer:

All Bette’s stories have happy endings. That's because she knows where to stop. She's realized the real problem with stories—if you keep them going long enough, they always end in death.

This sense of the ultimacy of death pervades the series. As Death says in Dream Country (vol 3 of The Sandman):

“When the last living thing dies, my job will be finished. I'll put the chairs on the tables, turn out the lights and lock the universe behind me when I leave.”

A corollary of this is that The Sandman is anti-wish-fulfilment. This is in contrast with much of the fantasy genre, which frequently deals in ‘escapism’ and wish-fulfilment fantasies. Superhero stories let us imagine being strong and powerful, benevolent and protecting. Space opera lets us imagine we are piloting spaceships and saving the galaxy. Epic fantasy enables us to dream of being a noble warrior, heir to a kingdom, wooing the princess. I could go on.

I don’t believe that wish-fulfilment in storytelling is necessarily harmful. Imagining ourselves as heroes can help prepare us to better use whatever power we do have in the real world for the good of others. Escapism can be a means to escape the limits of our present reality in order to reshape it.

But when escapism becomes a way of avoiding reality, it becomes a problem. Neil Gaiman isn’t content to pander to our wish-fulfilment, but confront us with questions about the costs of what we imagine.

The Tragedy of Death

One of the most ancient and enduring dreams that humans have is that of escaping death. We long for happy endings, for a time when “everything sad comes untrue”, as Samwise Gamgee says at the end of The Lord of the Rings.

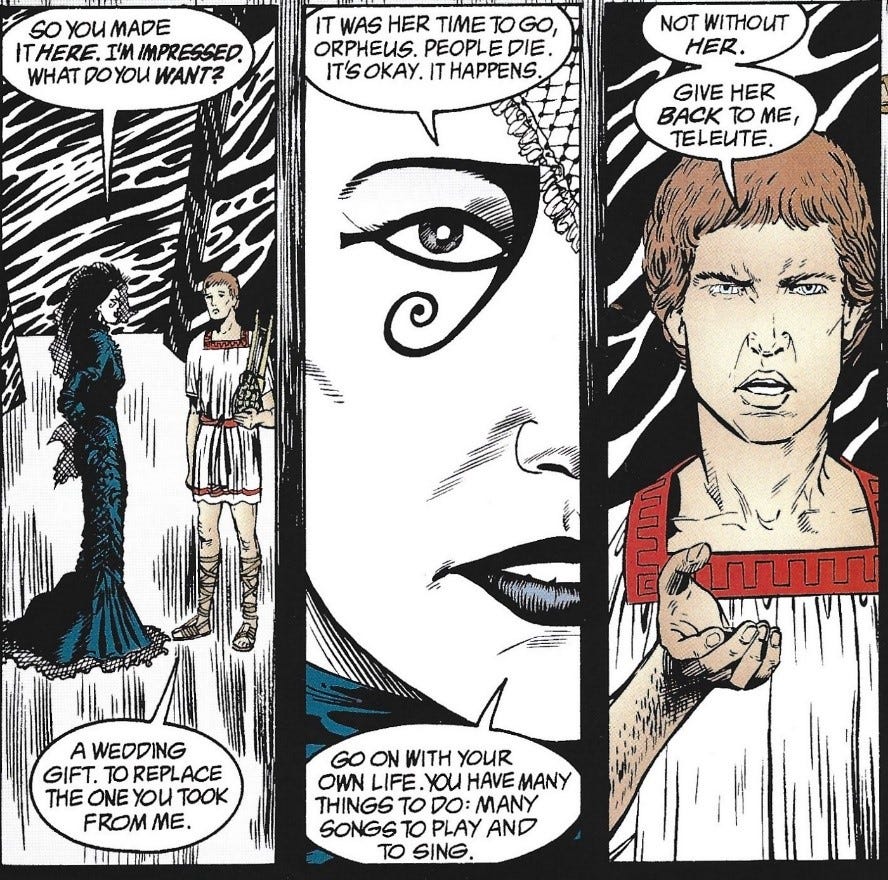

At the same time, many of our stories are warnings about the folly of attempting to avoid death. The Sandman begins with an occultist trying to trap death for his own purposes and unsurprisingly it does not end well. One of the ancient myths that The Sandman retells is the Greek tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice.

Orpheus was the son of Apollo (or of Morpheus in Gaiman’s version) and the muse Calliope. His music had such beauty to be able to enchant anyone, whether enemy or beast. He fell in love with and married Eurydice, but she died from a snake bite. Orpheus descended into the underworld to try to bring her back alive, and his music had such beauty that even Hades was moved to pity, and told him that Eurydice could follow Orpheus back to the land of the living, on condition that Orpheus not look back. But Orpheus began to doubt the gods, and looked back at the last moment, only to lose her forever. This myth has an enduring power in its themes of love and loss, and the power and limits of art and beauty to mend our griefs.

As Reality and Other Stories explores, death and resurrection is likewise central to the Christian story. Yet unlike the story of Orpheus, or the narrative of The Sandman, Death does not have the ultimate word. Rather, Jesus overcomes the monster that is death, by dying on the Cross and being raised to new physical life again. Because Jesus’ death was the sacrifice that paid for our sins, and death is the penalty for sin, humans can be free from the power of death by faith in Jesus – faith that unites us to his death and resurrection.

Orpheus was the son of Apollo (or of Morpheus in Gaiman’s version) and the muse Calliope. His music had such beauty to be able to enchant anyone, whether enemy or beast. He fell in love with and married Eurydice, but she died from a snake bite. Orpheus descended into the underworld to try to bring her back alive, and his music had such beauty that even Hades was moved to pity, and told him that Eurydice could follow Orpheus back to the land of the living, on condition that Orpheus not look back. But Orpheus began to doubt the gods, and looked back at the last moment, only to lose her forever. This myth has an enduring power in its themes of love and loss, and the power and limits of art and beauty to mend our griefs.

As Reality and Other Stories explores, death and resurrection is likewise central to the Christian story. Yet unlike the story of Orpheus, or the narrative of The Sandman, Death does not have the ultimate word. Rather, Jesus overcomes the monster that is death, by dying on the Cross and being raised to new physical life again. Because Jesus’ death was the sacrifice that paid for our sins, and death is the penalty for sin, humans can be free from the power of death by faith in Jesus – faith that unites us to his death and resurrection.

The Divine Comedy

The story of Jesus, in fact, taps into the longings at the heart of each of the seven basic plots. There is the rags to riches story of how Jesus’ brings the poor and lowly of the world and makes them heirs of the kingdom of God. Jesus calls us on the quest to follow him as his disciples, just as he came on a quest to seek and save lost humanity. He is on a voyage and return from Heaven to Earth, so that we like the Prodigal Son can make the return to God. He warns of the tragedy of life lived for self, rather than for love of God and neighbour. His death and resurrection is the story of Rebirth, that brings us to the divine comedy of all things being redeemed and restored through Jesus becoming king.

As Reality and Other Stories says:

Something within us senses that, however broken things are, however far tragedy’s effects have reached into our culture and however hopeless things may seem, the universe is made not just for uplifting endings here and there but a great happy-ever-after.

Such hopes seem unrealistic and wildly improbable. Given the pain in our lives, a universe that can be lethal to us and the foul bent to human nature, can we really believe that ‘everything sad will come untrue’?

Only if our hope is resurrection sized.

But a resurrection-sized hope is enough to change the story of the whole universe from tragedy to comedy.

Is the Gospel story just wishful thinking?

But is the Christian story just another example of wishful thinking? It’s important to interrogate the story with that possibility in mind. It isn’t enough to believe a myth just because we find beauty in it.

As The Sandman reminds us through Morpheus’s frequent moments of cruelty or indifference to humans, dreams can hurt and kill. Think of the stories of nation or religion or ideology that people have fought and died for over the centuries. Dreams can imprison, trap us in personal or social narratives that oppress. Sadly, many forms of Christianity have been and continue to be vehicles for oppression and repression of our full humanity.

One of the themes of The Sandman is our relationship to the stories we find meaning in. The Sandman is a postmodern myth, in that it examines how we can’t do without stories, but we can change our conception of stories, to be ‘suspicious of metanarratives’, of grand universalising claims to absolute truth. We can recognise the contingency of stories, and rather than treating them as absolute regardless of human cost, we can change our stories to be more humane, more in keeping with out human flourishing. (Of course, that idea of ‘human flourishing’ is another story – it’s stories all the way down…) Perhaps there can be a kinder, gentler version of Dream, more human and less capricious.

But what if there is a myth, a meaning-giving story, that really is true? What if meaning and fact, story and history, mythos and logos have found their meeting point in Jesus?

It might seem that this is just a backdoor to bring back in the totalising claims to authority, the oppression and repression of religion. But in the story of Jesus, God isn’t the lofty tyrant, but a self-giving saviour, one who triumphs through self-sacrifice and love of his enemies, overcoming evil, death and injustice. The Christian story is radically subversive of any version of Christianity that seeks to prop up oppression or underwrite an unjust status quo. What if this is a myth that is both objectively true and good?

Myth Become Fact

Reality and Other Stories continues:

If the stories we tell really do reflect our innate desires – and they really are homing devices, drawing us into the reality for which we were made – we should expect fictional stories to echo themes of the real one. The difference is that the story of Jesus is, as C.S. Lewis concluded when he surrendered his agnosticism for Christianity, ‘myth become fact’. It really happened.

We should not feel ashamed or patronized by the fact that truth comes to us in story form. God’s appeal to us through story shows that he wants to be known: he addresses us in one of the most culturally transferrable forms. He also addresses us as humans, those who make sense of our experiences by means of story. As J.R.R. Tolkien wrote, it is fitting that ‘Man the story-teller would have to be redeemed in a manner consonant with his nature: by a moving story.’

We should not despise the fact that Christianity’s claim to truth comes by means of story – instead we should ask ourselves the next question … ‘Could it be true?’

As Reality and Other Stories points to at the end, and which many other books, such as brief overview Resurrection: Fact or Fiction? by Richard Cunningham or in more depth in The Historical Reliability of the Gospels by Craig L Blomberg explore in more detail, there is much in the Gospel narratives that commend them to us as an honest historical record, an attempt to record the miracle of God making himself known through Jesus, and defeating the power of death so that we can be remade spiritually and one day experience everlasting life.

But what about you? Which story do you believe is the story of reality?

One where death is the ultimate reality, though perhaps one to be met as a friendly face, like the Death of the Endless? Or do our stories expressing a long for hope beyond death point us to something in reality?

Let me know in the comments your take on The Sandman and the nature of myth and reality - I’d love to hear your viewpoint, whatever viewpoint, faith or philosophy you are coming from!

Life is a reality show, a drama and we all are programmed actors, all the seven stories are true. Jesus's resurrection is not true, he fled along with Mary Magdalene towards east and came to India. His real tomb is in Kashmir. As he also believed in Sanatan dharma and learned from Buddhism philosophies during his 18 years of undocumented history. He also knew that everything originated from Bharat and must end at Bharat only to be whole or complete the kaalchakra or cycle. That's why zero was invented in Bharat.